preCICE allows the participants to use subcycling – meaning: to work with individual time step sizes smaller than the time window size. Note that participants always have to synchronize at the end of each time window. If you are not sure about the difference between a time window and a time step or you want to know how subcycling works in detail, see “Step 5 - Non-matching time step sizes” of the step-by-step guide. In the following section, we take a closer look at the exchange of coupling data when subcycling and advanced techniques for interpolation of coupling data are used inside of a time window.

Exchange of coupling data with subcycling

preCICE only exchanges data at the end of the last time step in each time window – the end of the time window. By default, preCICE only exchanges data that was written at the very end of the time window. This approach automatically leads to discontinuities or “jumps” when going from one time window to the next. Coupling data has a constant value (in time) within one coupling window. This leads to lower accuracy of the overall simulation.1

Example for subcycling without waveform iteration

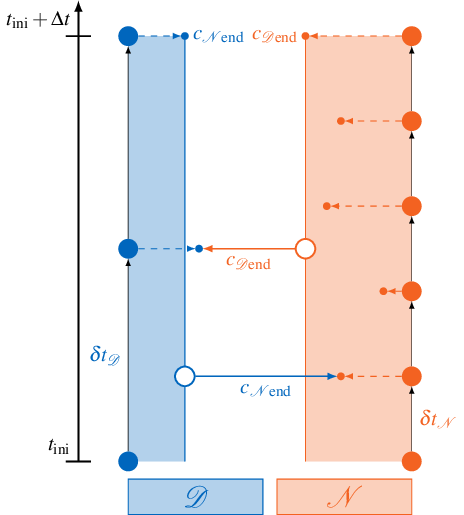

The figure below visualizes this situation for a single coupling window ranging from \(t_\text{ini}\) to \(t_\text{ini}+\Delta t\):

The two participants Dirichlet \(\mathcal{D}\) and Neumann \(\mathcal{N}\) use their respective time step sizes \(\delta t_\mathcal{D}, \delta t_\mathcal{N}\) and produce coupling data \(c\) at the end of each time step. But only the very last samples \(c_{\mathcal{N}\text{end}}\) and \(c_{\mathcal{D}\text{end}}\) are exchanged. If the Dirichlet participant \(\mathcal{D}\) calls readData, it always reads the same value \(c_{\mathcal{N}\text{end}}\) from preCICE, independent from the current time step.

Linear interpolation in a time window

A simple solution to reach higher accuracy is to apply linear interpolation inside of a time window to get smoother coupling boundary conditions. With this approach time-dependent functions (so-called waveforms) are exchanged between the participants. Since these waveforms are exchanged iteratively in implicit coupling, we call this procedure waveform iteration. Exchanging waveforms leads to a more robust subcycling and allows us to support higher order time stepping.1

Example for waveform iteration with linear interpolation

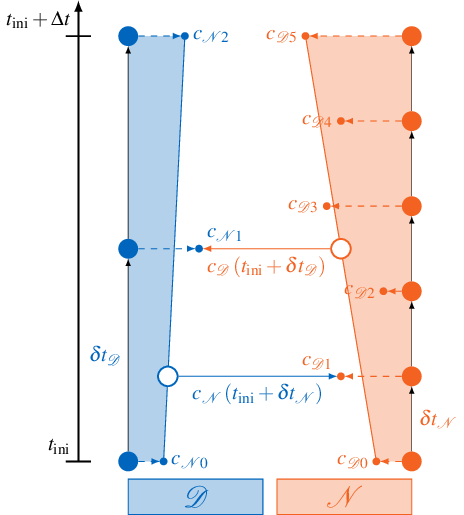

Linear interpolation between coupling boundary conditions of the previous and the current time window is illustrated below:

If the Dirichlet participant \(\mathcal{D}\) calls readData, it samples the data from a time-dependent function \(c_\mathcal{D}(t)\). This function is created from linear interpolation of the first and the last sample \(c_{\mathcal{D}0}\) and \(c_{\mathcal{D}5}\) created by the Neumann participant \(\mathcal{N}\) in the current time window. This allows \(\mathcal{D}\) to sample the coupling condition at arbitrary times \(t\) inside the current time window.

Using waveform iteration

preCICE requires the argument relativeReadTime for the readData functions:

void Participant::readData(

precice::string_view meshName,

precice::string_view dataName,

precice::span<const VertexID> vertices,

double relativeReadTime,

precice::span<double> values) const

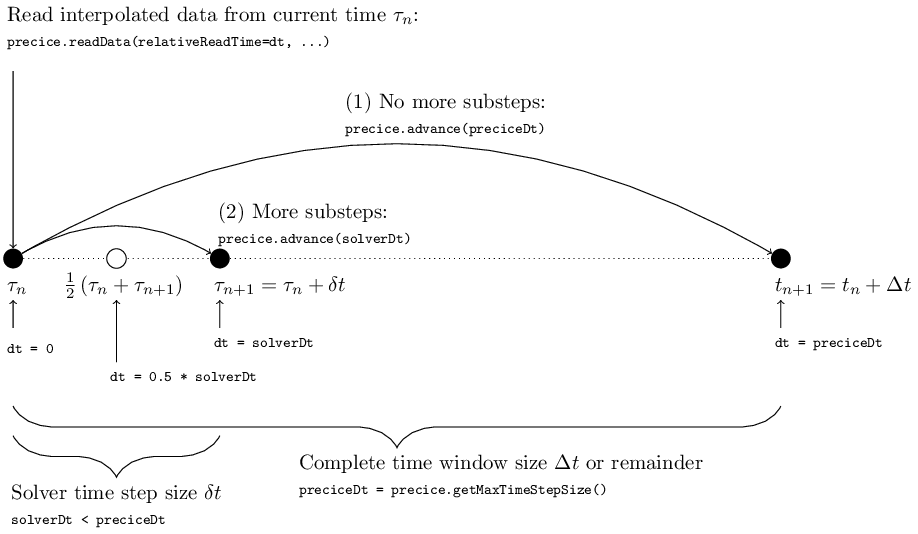

In the previous sections of the step-by-step guide we always used relativeReadTime = preciceDt where preciceDt = precice.getMaxTimeStepSize() points to the end of the current time window (see, for example “Step 5 - Non-matching time step sizes”). However, the original purpose of relativeReadTime is exactly to offer the user an interface for sampling from waveforms. The figure below illustrates how providing different values dt for relativeReadTime allows to sample interpolated values at different points in time:

relativeReadTime describes the time relatively to the beginning of the current time step starting at \(\tau_n\). This means that dt = 0 gives us access to data at the beginning of the time step. By choosing dt > 0 we can sample data at points in time after \(\tau_n\). The maximum allowed dt = preciceDt corresponds to \(\tau_n\) plus the remaining time until the end of the current time window (i.e. preciceDt = precice.getMaxTimeStepSize()).

If we choose to use a smaller time step size solverDt < preciceDt, we apply subcycling and therefore dt = solverDt corresponds to sampling data at the end of the time step. But we can also use arbitrary values for dt, like dt = 0.5 * solverDt to implement, for example, a midpoint rule (see also the usage example below).

This allows us to define the degree of the interpolant in the read-data tag of the corresponding participant. Currently, we support two interpolation schemes: constant and linear interpolation. The interpolant is always constructed using data from the beginning and the end of the window. The default is constant interpolation (waveform-degree="1"). The following example uses waveform-degree="3" and, therefore, cubic interpolation:

<precice-configuration ... >

...

<data:vector name="Forces" waveform-degree="3"/>

<data:vector name="Displacements" waveform-degree="3"/>

...

</precice-configuration>

Availability

Depending on the used coupling scheme, time interpolation may not always be available. The following table shows when it is available, which without further changes means linear interpolation between the data samples at the beginning and the end of the window. Note that due to the staggered nature of serial schemes, time interpolation is always available in the participant that goes second. This is the only instance where time-interpolation is available in an explicit coupling scheme.

| Coupling scheme | First iteration | Later iterations |

|---|---|---|

| serial-explicit | second only | |

| serial-implicit | second only | yes |

| parallel-explicit | no | |

| parallel-implicit | no | yes |

| multi | no | yes |

For higher-order interpolation, some additional steps need to be taken:

- The solver writing the data needs to perform multiple sub-steps per time-window to generate samples to interpolate from,

- the coupling-scheme needs to exchange the substeps of data from the writing to the reading solver with

<exchange ... substeps="true" />, and - the data needs to use a higher waveform-degree, for example

<data... waveform-degree="3"/>.

Note that preCICE generates an interpolant of lower degree if there are not enough samples available. Please ensure that the writing solver generates at least the amount of samples equal to the requested waveform-degree.

Usage examples

Midpoint rule

We are now ready to extend the example from “Step 6 - Implicit coupling” to use waveforms. Let us assume that our fluid solver uses a midpoint rule as time stepping method. In this case, only few changes are necessary to sample the Displacements at the middle of the time window:

...

precice.initialize();

while (not simulationDone()){ // time loop

// write checkpoint

...

preciceDt = precice.getMaxTimeStepSize();

solverDt = beginTimeStep(); // e.g. compute adaptive dt

dt = min(preciceDt, solverDt);

// sampling in the middle of the time step

precice.readData("FluidMesh", "Displacements", vertexIDs, 0.5 * dt, displacements);

setDisplacements(displacements); // displacement at the middle of the time step

solveTimeStep(dt); // might be using midpoint rule for time-stepping

computeForces(forces);

precice.writeData("FluidMesh", "Forces", vertexIDs, forces);

precice.advance(dt);

// read checkpoint & end time step

...

}

...

Different time scales

For solvers operating on different time scales, the solver with the smaller time-step size may not work with constant input data over the entire time-window.

In cases where time-interpolation is available, the solver with the smaller step size may call readData() with relativeReadTime=0 to sample data at the beginning of each of its time steps.

By default, this results in piecewise linearly interpolated data. To achieve higher-order interpolation, the solver with the larger time-steps can now perform multiple time-steps per time-window to provide additional samples.

Literature

-

Rüth, B, Uekermann, B, Mehl, M, Birken, P, Monge, A, Bungartz, H-J. Quasi-Newton waveform iteration for partitioned surface-coupled multiphysics applications. Int J Numer Methods Eng. 2021; 122: 5236– 5257. https://doi.org/10.1002/nme.6443 ↩ ↩2